We are grateful to local resident Maurice Bennington for sharing his photographs and family stories with us. Maurice is the great nephew of Ernest and Walter Bennington who, together with their step-brother, Alfred Watson, served in the First World War.

Walter Henry Bennington was born in 1892 (birth date given as 24th June 1892 in Carleton Rode School Register), the youngest of eight children born to Edward and his first wife Anna Maria. The family lived in Runhall, a village about half-way between Dereham and Wymondham, where Edward worked on the land. Official records tell only a part of the family story and we are fortunate that greater access to newspaper accounts give us a real flavour of life in the Bennington family in this period – and perhaps helps us to better understand Walter’s actions during and after the First World War.

Edward and Anna’s first child, Mildred, was born in 1877 before the couple married and she spent her first few years living with her maternal grandparents. Edward married Anna before their second child was born in 1880; Anna could read and write – Edward was illiterate. To supplement the family income, Edward was caught poaching with another farm labourer and two dogs (lurchers) on the Earl of Kimberley’s estate. An account of the crime is published in the Norwich Mercury on Christmas Eve in 1881 and records that the labourers were fined £2 each or a month’s imprisonment – a large sum when you consider that a farm labourer’s weekly wage was about 12 shillings at the time.

Six more children were born to the couple over the next decade. Tragically, Anna died aged just 32 in 1893 when the youngest, Walter, was only a year old. She is buried in Runhall churchyard. No doubt that supporting eight children on Edward’s meagre wage, life would have been difficult. The older girls were aged 16, 14 and 12 at the time of their mother’s death and would have had to take over her household tasks, as well as bringing up their younger siblings. School registers show that the family left Runhall soon after Anna’s death and we know that they were living in the Wymondham area by the next census.

However, for a few years in the second half of the 1890s, the family moved to a village near Loddon where Edward worked as a shepherd. Ernest left school at this point and found a job working – and boarding – on a farm along Pye’s Mill Road to the north of the town. Living nearby, and recently widowed with a young family, Emily Watson met Edward Bennington. In April 1898, Emily gave birth to a son they named Edward Reginald – although the birth is not officially registered. An insight into their lives appeared in a newspaper account of the petty sessions for the following summer, published in the Norwich Mercury on August 8th, 1899 and retold below.

Edward and his wife, Emily (more of this later), were living near the church in Carleton St Peter and next door to John Preston, a market gardener. It seems that a long running dispute between the neighbours came to a head and two charges are brought before the court. Firstly, John Preston was accused by Edward of using obscene language – for which the market gardener was found guilty and fined 2 shillings and costs. Then at the same sessions, John Preston accused Emily Bennington of assault by throwing a pail of water over him. The bench, whilst remarking that such a ‘miserable squabble’ should never have been brought before them, found Emily guilty of a technical assault and fined her the same amount (but without costs). Perhaps it is not surprising that the Benningtons moved back to the Wymondham area soon afterwards.

Less than a year later, a tragedy befalls them.

From the Eastern Daily Press 30th May 1900

SAD DEATH OF A CHILD

An inquest was held at Wymondham yesterday afternoon on the body of Edward Reginald Bennington, aged 1 year and 11 months, who met with his death by drowning on Saturday.

Edward Bennington, yardman, of Downham identified the body as that of his son. Witness’ wife, the mother of the deceased, went to Norwich on Saturday, and witness said he would see after the deceased. He last saw the deceased alive at three o’clock on a private farm road near his house, and on Mr Webster’s farm, in whose employ witness was. At that time the deceased was with his half-brother, witness’ child by a previous marriage, aged eight. They were picking daisies, and witness told them to stay there until he returned from a job of work. At four o’clock deceased’s half brother came to witness crying and said deceased was drowned in the pit by the side of the road. Witness went to the pit at once and found that the body of the deceased had been taken out and home. When he reached home he found that the deceased was dead. Efforts were made to restore animation but without success. The life of the child was not insured and he had had no other child die.

William Land, aged 15, farm labourer, said on Saturday afternoon that he was at work in a field near the pit in which the deceased was drowned. At a quarter past four he heard deceased’s brother shrieking and saw him go in the direction of his father. Witness asked him what was the matter, and he said his brother had fallen into the pit. Witness then went and told his own father, who was at work in the field adjoining the pit, and witness, his father, and other men went to the pit, where they saw the body of the deceased floating on the top of the water. Deceased appeared to be dead.

William Land, the elder, and John May, both of them employed by Mr Webster, described the manner in which they took the body out of the water and then tried to restore animation, and the jury found that the deceased was accidentally drowned through having fallen into the pit.

Walter was the 8-year-old half-brother left in charge of the toddler Edward that day – something that would not have been unusual for the times (but what an appalling experience to have to cope with) and we can only surmise the impact that it had on all involved.

In the following year’s census, Emily and her two youngest children were living with Edward and three of his children – still on the same farm at Downham – a hamlet on the outskirts of Wymondham. Although she was known as Emily Bennington and described as Edward’s wife on the census (and in the above newspaper articles), we know that the couple did not actually marry until 1926; a marriage between Edward Bennington and Emily Watson is registered in Mutford district (which at the time incorporated all the border of Norfolk and Suffolk between Thetford and Lowestoft) – and not in Depwade district where the couple lived.

The family moved to Carleton Rode in the autumn of 1904; Walter and Alfred Bennington (Watson) were admitted to the village school in October. The following summer, Walter was put forward to take the Special Labour Certificate Exam which he would need to pass to be allowed to leave school that year. However, he was not successful and had to take it again in 1906. After leaving school, Walter became a fisherman working in Great Yarmouth before he followed in his older brother Ernest’s footsteps and signed up for the army at the beginning of 1910. He joined the 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment as a machine gunner, service number 8156, and was based at the Malplaquet Barracks in Aldershot.

In 1912, following Prime Minister Asquith’s announcement of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland, Walter, as part of the 1st Battalion, was sent to Belfast (Holywood Barracks) where the Regiment was engaged in helping to keep the peace as Unionists began to protest, raising armed resistance in Ulster. At this point, Walter was promoted to Lance Corporal. During his time as a regular soldier, Walter’s conduct record was mixed. Offences ranged from not saluting an officer, lying to an NCO, frequently absent without leave, missing parade, disobeying orders, overstaying furlough and even resisting arrest – and although he was deprived of his Lance Corporal rank and returned to being a private, his conduct was still officially described as ‘fair’. Whilst serving in Belfast, Walter met a local girl, Lily Nelson, from Ballyclare, County Antrim – but then the situation in Europe erupted into war.

Within a few days at the start of August 1914, Germany had declared war on Russia and France – and invaded neutral Belgium. Great Britain demanded the Germans withdraw but following the Kaiser’s refusal, Great Britain declared war on Germany on the 4th August. The 1st Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment, including Walter Bennington, as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), received immediate orders to depart for France.

The Regiment’s war diaries record that the battalion left Holywood Barracks on the 10th August and six days later landed at Le Havre, the first base camp to be established in France. Unfortunately, the pages for August and September are missing, but we know from Walter’s army record (which only partially survives) that he was in action on the 24th August at the Battle of Mons.

The Ist Battalion had been sent to the eastern French border (together with the 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment) with orders to take up a defensive position just outside of Mons between Audregnies and Elouges where four German regiments were advancing across open fields. The Cheshires and Norfolks were heavily outnumbered but their rear-guard actions bought valuable time for the retreat of the BEF from the area – albeit at huge cost.

Three thousand British soldiers were killed or wounded in the retreat, indeed whole units disappeared. In their section, the Cheshires lost 771 men and the Norfolks left behind a hundred wounded or worse. They were the last platoon remaining and with no senior officer able to take charge, they held on fighting alone and isolated. Lyn Macdonald’s 1914 The Days of Hope (published by Penguin 1987) brilliantly describes those early months of the Great War and brings to life what it was like for those ordinary soldiers (like Walter) by drawing on a vast collection of eye-witness accounts; letters, diaries and journals.

In the confusion and chaos of the aftermath, and in the continuing actions of the long withdrawal of the BEF, Walter was reported missing. Presumably, he and others from what was left of the battalion, joined up with other foot soldiers from decimated units, as it took him three weeks to make his way back to the 5th Infantry Base Depot, which had just been moved to St Nazaire (Le Havre was evacuated in early September following the German army’s success at the Battles of Mons and Le Cateau). This involved moving over 22,000 personnel, 3,500 horses and over 65,000 tons of supplies. It was against this backdrop that Walter reported for duty on the 10th September.

Within two days of his return, he was promoted – first to acting Corporal and then Sergeant (clearly, Walter’s military experience was recognised – especially given that so many of his comrades had been killed, wounded or captured). Two weeks later, Walter rejoined his battalion at the front on the 26th September. In the intervening two weeks, the 1st Norfolks had been involved in the Battle of the Aisne where most of the BEF were engaging the enemy and had become entrenched. A long strip of land became a stalemate with neither side able to take control. Trench warfare was a new concept that was quickly developed by both armies – and over the course of the war, eventually became a continuous system of trenches that stretched for 400 miles from the sea at Nieuwpoort in Belgium to the Swiss border, east of Belfort.

During this period, Walter’s brother, Ernest, who had been a regular soldier serving overseas for many years with the 2nd Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment, rejoined the Norfolks at the outbreak of war and was posted to the 1st Battalion, arriving in France on the 22nd August. Letters written home by Ernest vividly describe the regiment engaged in some of the heaviest fighting during the first months of the war. He was also fighting alongside his brother when Walter was wounded at the Battle of La Bassée in October. Suffering from a gunshot wound to his left thigh, Walter was transferred by hospital ship, the St David, back to Britain for treatment.

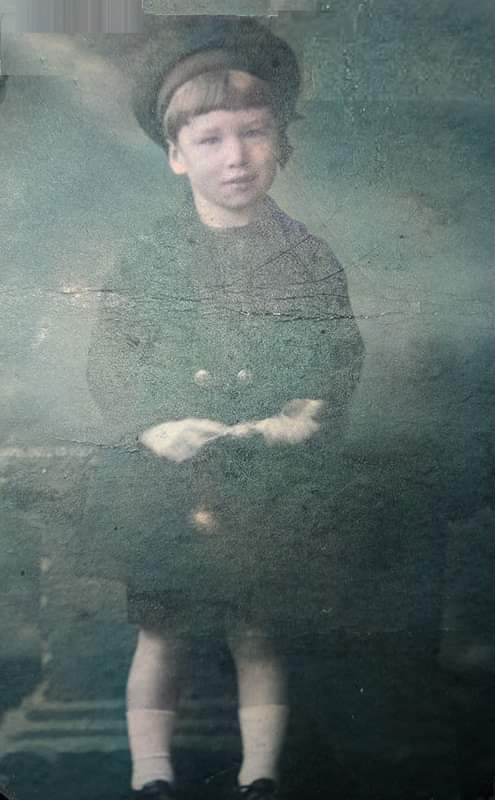

There is a photo in his great-nephew’s collection that we believe was taken just before Walter was discharged from a military hospital. It shows a group of soldiers from a variety of different regiments (judging by their cap badges) and looking ready to return to action. We think that Walter, with his sergeant’s stripes, is seated on the second row, 5th from the right.

We surmise that he spent some time with his family in Carleton Rode during his recovery as he was punished for overstaying leave and being absent from Parade at the Norwich Barracks in February, 1915. Just over a month later, he was posted back to France and joined the battalion south-east of Ypres where they spent two weeks alternating with the Cheshires in the front-line trenches. They came under heavy shelling and suffered several casualties before being moved to the reserves. After two weeks, the battalion returned to the trenches south of Ypres in the build up to the Battle for Hill 60 which had been held by the enemy since the previous November. It is during this period that Walter received a gunshot wound to the head. He was taken by field ambulance to the base hospital at Poperinghe, west of Ypres, before being repatriated back to Britain nine days later. (Lance Sergeant W Bennington 8156 was reported as wounded in newspapers published both in Norfolk and Belfast.)

And this is where Walter’s story becomes more complicated.

The army documents state that Walter deserted the army on the 1st June 1915. However, several letters from the British Legion office in Belfast (although partly burned) survive as part of his army service records and they allow us to see a much more nuanced picture of what happened next.

Following hospital treatment for his head injuries, Walter was sent to Felixstowe where the 3rd Battalion Reserve was stationed. He became involved in an argument with an officer and disappeared – hence the desertion charge. Walter may well have taken refuge for a while with his father and family back in Norfolk as it is not that far from Felixstowe. But it seems that he then made his way to Belfast where he had previously been stationed as his marriage to Lily Nelson was registered in the city in the summer of 1916. According to the letters, he signed up for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve where he was appointed a Petty Officer and ‘sent out east’ (sic). Before Walter joined the regular army, he had spent two years at sea as a fisherman, so volunteering for the RNVR would seem perfectly plausible.

The surviving fragments of letters were written by a J Carson, Secretary at the British Legion in Belfast, and these relate how Carson met Walter in the RNVR during the war and that he knew his history well. The letters to the War Office in London were written in 1928 and are on behalf of Walter’s wife, Lily, who is in ‘a delicate state of health’ and in need of support – specifically housing. The British Legion were especially concerned with providing homes for ex-servicemen and their families. Mr Carson also stated that Walter’s behaviour had been seriously affected by his war injuries, especially the head wound and that his conduct had been ‘erratic ever since’. He was no longer in Belfast and had gone to Scotland in search of work. It is quite clear that Mr Carson believed that the Army knew of Walter’s situation when he volunteered in Belfast as the RNVR had been in contact with the base at Felixstowe at the time.

However, the response from the War Office appears to be unequivocal – he must confess to desertion or face a court-martial. Either way, the penalties would have been severe, probably imprisonment with hard labour. So, what happened next? We simply don’t know – there is nothing else in his service records, and nothing in the RVNR records to suggest that Walter served with them (and not be confused with a *William Edward Bennington, born in 1894, a Petty Officer in the RNVR and based at HMS Crystal Palace, who at one point was also listed as a ‘deserter’!) *Editor’s note: We now know from Walter’s great-grandson, who is in possession of his naval papers, that this man is indeed Walter – and he used different first names when he joined. The names he used are those of his father and uncle!

Although official documents for Northern Ireland are more difficult to access than those for England, there are two intriguing records to consider. A John Carson Bennington’s birth was registered in Belfast during the first quarter of 1920. There is also a burial record for an 8 week-old baby named Walter Bennington in Belfast City Cemetery in 1922; the address given is 20 Ravensdale Street – exactly the same as Walter’s wife in the letters written by the British Legion official (John Carson?) some six years later.

We know that Walter’s fascinating story does not end here – and hope that any descendants reading this will get in touch with us.

My Father was John Carson Bennington who was born in 1920 ,Walter Bennington was my Grandfather , Walter Bennington went on to have three sons John Carson Bennington, Ernest Edward Bennington and Nelson Bennington . My Father John Carson had 11 Children , Ernest Edward had 3 Sons and Nelson had 1 son.

Walter Bennington was my great grandfather, and I have his navel records. He signed up at Crystal Palace and ended up serving on the HMS Perth. He also worked for Shorts & Harland in Belfast during the second world war, which was where many British fighters and bombers were built.