Robert’s birth was registered at the beginning of 1884 and he was baptised in Carleton Rode Church on March 24th of that year. His parents were George and Elizabeth Bush. George had moved into the parish as a small boy with his family in the mid-1860s and although born in Hinderclay, Suffolk, he would have found many of his relatives in the village (and buried in the churchyard) as his great-grandfather had moved into Carleton Rode around 1800.

George and Elizabeth were married in Carleton Rode Church in 1879 and went to live on Flaxlands. They were eventually to have ten children over a period of 21 years – seven of whom were born in the village: Rosa Ellen (1880), George Watson (1881), Frederick William (1882), Robert Thomas (1884), Frederick John (1886), Amelia (1887/8) and Ethel Maud (1890). All the children except Amelia were baptised in All Saints (Carleton Rode) and tragically two of them were buried there in the summer of 1884 – Rosa, aged 4, on the 9th July and Frederick William, aged 2, on the 16th July.

In 1890 whilst living on Flaxlands, Elizabeth Bush witnessed the tragic death of a vulnerable young man – the following report appeared in the Diss Express in May, 1890.

Life could be very precarious for the poor and scenes like this were not uncommon – Albert Neave had only recently been released from prison and there would have been little support for ex-offenders during this period. The Bush family were also about to experience very difficult times.

George, an agricultural labourer (and in common with most farm workers during this period) would have found it difficult to make ends meet. Farming was economically depressed. At the time of his marriage, the average farm labourer’s wage was around 14 shillings per week – after which it steadily decreased – and the growing family would have been living on 13 shillings in the mid-1880s. We know from a later property sale reported in the EDP that George was a tenant paying a yearly rent of £5 – which works out at a weekly rent of approximately 2 shillings – leaving the family 11 shillings for everything else, a meagre amount even then (difficult to relate to today’s prices, but many sources agree that an average family at this time would need around 20 shillings a week to meet the cost of rent, food, fuel and other basic necessities).

Perhaps it is no surprise that by the 1891 census, things have taken a turn for the worse for George, Elizabeth and their offspring.

We find Elizabeth living in Bunwell with her five surviving children aged between 1 and 10 years, now described as a pauper and dependent on parish relief (she had been born in the village). George is incarcerated in the then new Norwich Prison (opened in 1887 on Plumstead Road next to the Headquarters of the Norfolk Regiment at Britannia Barracks) – not sure yet as to the reason or the length of sentence. What we do know is that he was on the Register of Electors for Flaxlands, Carleton Rode and then Great Green, Bunwell in 1890/1891 and then again in 1893 – so it seems likely that he served between one and two years.

When he is released, the family move to a cottage on ‘The Marsh’ in Wreningham. Another child is born to them, Christina Alice on the 12th December, 1896. The school leaving age at this time was 11, and so by now the two older sons will also be working to supplement the family income. Two years later, the family move again to Barford where Blanche Olive is born on the 6th February 1899. Within a year, they have relocated to Dunston and in the 1901 Census they are living (and presumably working) at Betts Farm near the Common – all three older boys, George, Robert and Frederick are agricultural labourers. This is also the year that George and Elizabeth have their final child, Dorothy May, born on the 22nd August. The couple and their younger children remain in Dunston for another four years before returning to the Bunwell/Carleton Rode area – first living on The Fen (Bunwell Low Common) and then on the Turnpike road before settling in Bunwell Bottom.

So, what happens to the older boys? George Watson (he’s known as Watson on the 1901 census) moves to Norwich around 1903/4 before emigrating to Canada a few years later.

Robert finds agricultural work in Kenninghall and enlists as a reserve ‘Militiaman’ in the 4th Volunteer Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment. The part-time nature of the role suited agricultural and other casual labourers as they would train for perhaps two or three weeks per year – and the militia camps would have provided a welcome change of routine, and extra pay too.

However, when Robert signed up in late 1906, there were already moves afoot to reform the army and this resulted in the abolition of the militia in 1908 and the formation of the Special Reserve. Robert is discharged in February of that year having completed 49 days’ training and he does not appear to have re-signed for the Territorial Force.

The next record we have of Robert is on the 1911 Census when he has moved to the East Yorkshire Wolds and is living and working as a cattleman for the Morris family in Frodingham Bridge, near Driffield (and the Morris family continued farming at Bridge Farm until 2019). As a boarder, Robert would not have been entitled to vote and therefore we cannot trace him through the electoral records.

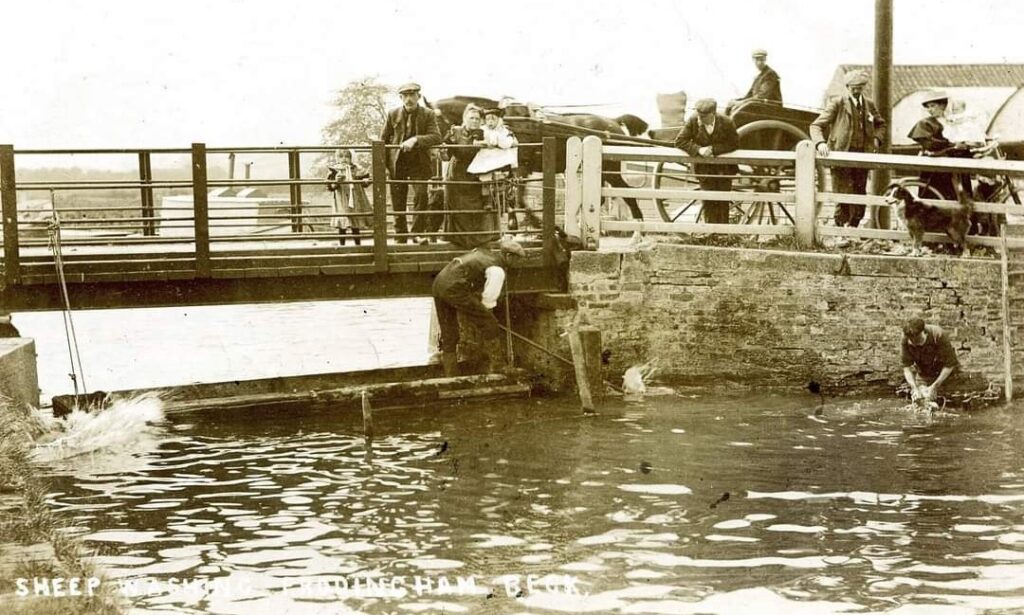

We are extremely grateful to Sam Morris for sending us this image taken c1910 when Robert was working for Sam’s great, great grandad, Nathan Morris (pictured centre, below the bridge). It is so wonderful even to get a glimpse of Robert, let alone one of such an evocative scene of days long gone.

As an interesting aside, the barn at Bridge Farm where Robert was living also appeared in the 1911 census:

For the first time, the government of the day (initiated by the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill), attempted to make an approximate count of the homeless – officially recorded by the police and not the normal census enumerators. The police, who usually knew all the locations where homeless people stayed the night, were ordered not to make this an excuse for the persecution of the homeless – just record the information. Special census forms were issued and the police were instructed to search for those sleeping in ‘a barn, shed, kiln, etc., under a railway arch, on stairs accessible to the public, or wandering without a shelter.’ What had happened to George Rayner for him to be sleeping rough on that April night?

Robert’s army attestation papers for the First World War do not survive. We know from ‘Soldier’s Died in the Great War 1914-1919’ that he signed up to the East Yorkshire Regiment in Hull (so he was still living and working in the area prior to 1914) and served in both France and Belgium. He is transferred into the Machine Gun Corps when it was formed in October 1915 and was part of the 64th company that joined the 21st Division and was involved in Battle of the Somme. He was killed during the capture of Gueudecourt on the 26th September 1916 – although his body was never recovered and he is simply referred to in the War Diary as ‘O/R 7’ (other ranks, 7 deaths) – suffering the same fate as the 72,000 men whose names are incised on the Portland stone panels of the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

After his death, Robert’s father (as his next of kin) was entitled to any back pay that had accrued – plus, after 1918, a war gratuity was introduced (a minimum of £2 if a man died). In total, George received just short of £8 from the government. At the time, an ordinary agricultural labourer would have earned about £1 10 shillings weekly (so £8 equates to around 2 months’ pay). For surviving soldiers returning home, this money was meant to help them back into civilian life. Countless ex-servicemen, promised a ‘land fit for heroes’ by the Lloyd George government, suffered when unemployment rose rapidly during the 1921 economic slump. Many of the agricultural labourers who took part in the 1923 Norfolk farmworkers’ strike had fought in the Great War (which is often seen as a watershed in the history of the English countryside).

George and Elizabeth were living in Bunwell Bottom at the time of Robert’s death, and despite being born and baptised in Carleton Rode, Robert’s name is not remembered on the roll of honour lists in either village. In 1920, the couple moved to Attleborough and lived near their eldest daughter and her family. George died there in 1927 but Elizabeth lived on until 1947.

It is testament to Tony Brook’s tenacity and determination over many years to make sure that his great-uncle’s sacrifice is not forgotten. We have taken up the torch and hope that we can finally ensure that Robert Thomas Bush is remembered in the village of his birth by adding his name to our War Memorial.

My grandfather was Fredrick Bush, brother of Robert. He too moved to East Yorkshire as a farm worker. Fredrick joined the East Yorkshire Regiment in Beverley, later to be transferred to the Machine Gun Regiment, we are lead to believe the mounted machine gun corps, he served in the Middle East and Belgium. My father was born in 1923 and was named George Watson Bush. If possible I would like to contact Tony Brook to find out

any other information on the Bush family.

Hi Peter, Not sure if you have made contact with me ?, (Tony Brooks). Did your grandfather return to Norfolk ? Watson George Bush moved to Canada and as i understand died there. I suspect your father was named after him.

Hi Peter, I think I may be a relative of yours , when I lived in Attleborough as a child, we had a family from Beverly in Yorkshire stay with us a few times, They were related to my mother, who’s mother was called Amelia Bush.

.Their name was George and Mary Bush who had two children Georgina and Peter., is it possible that it could have been you?

Hello firstly well done on the research a lovely read. Robert Bush would have worked for my great great grandad where we are still farming today!

I don’t have any other information on him unfortunately but I have a picture which Im fairly certain he is on I’ll have to send it to you.

I did write to your family some years ago about my great uncle, sadly never received a reply. It has been a long journey to place this together and finally have Roberts Name in Stone.